Were the BBC messages really announcing the Normandy landings?

The false legends of D-Day

Franck Bauer, one of the famous voices on the BBC’s Radio-London programme, including the famous ‘personal messages’ from the French who ‘speak to the French’.

Photo: DR.

The first false D-Day legend: ‘a message from the BBC announced the Normandy landings’.

The ‘personal messages’ of the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) never announced the Normandy landings, as I have regularly read or heard, particularly during commemorative periods. Imagine for a second that the Allies could have envisaged announcing over the airwaves, and in clear terms, that an assault by almost 150,000 men was imminent, without the certainty that their code would not be broken by the Germans…

Obviously, each message was intended for a group of resistance fighters (when the message wasn’t a false code designed to make German analysts work for nothing). There was nothing extraordinary about their meaning: they ordered the destruction of a bridge, triggered an ambush, announced a parachute drop or an arms delivery. Resistance fighters in one group were not aware of the meaning of a message intended for another group, in order to avoid information leaking out if the enemy recovered the code.

What was extraordinary in the week leading up to D-Day was the number of messages broadcast over the airwaves. Not ONE message announced THE landing. Let’s say it once and for all!

The second false D-Day legend: ‘The BBC broadcast Verlaine’s verses to announce the landings’.

The coded message ‘Les sanglots longs des violons de l’automne…’ had already been used in 1943 on Radio-London, for the benefit of the ‘Butler’ resistance network led by Jean Bouguennec, alias ‘Max’.

The first part of this message, ‘Les sanglots longs des violons de l’automne’ (‘The long sobs of autumn violins’), was broadcast by the BBC on 1 June 1944 as part of the programme ‘Les Français parlent aux Français’ (‘The French speak to the French’). This precise code was intended for Philippe de Vomécourt’s ‘Ventriloquist’ network, based in Sologne (south of Orléans). It alerted Resistance fighters to prepare to sabotage communication routes in their sector, on orders and within seven days of the message being sent.

The second part, ‘Bercent mon cœur d’une langueur monotone’ (listen to the original version at 1:40 here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VqXsgujDjOY), was broadcast on the same radio station on 5 June 1944 at 9.15pm Paris time, simultaneously with several dozen other codes. This message, still intended for the Ventriloquist resistance network, meant that sabotage operations in Sologne had to be carried out within 48 hours.

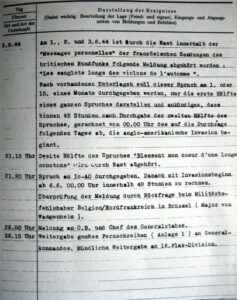

So, ‘Blessent’ or ‘Bercent’? It should be noted that the Germans copied the words of Verlaine’s original verses in their report of 5 June (version shown below, kept at the Tourcoing museum), specifying ‘Blessent’ but with a transcription error – ‘longueur’ instead of ‘langueur’ .

German diary of messages from the Resistance, kept at the Musée de Tourcoing.

Document: Tourcoing Museum.

This difference is explained in particular by the proximity of Verlaine’s poem to a song by Charles Trenet, who drew much of his inspiration from it to compose his own ‘Chansons d’Automne’, replacing ‘blessent’ with ‘bercent’.

This song, which was particularly popular in the 1940s, is most likely the source of the many inversions between ‘bercent’ and ‘blessent’ in our history books.

Charles Trenet’s song inspired another code tune broadcast on the BBC on 5 June 1944: ‘Les enfants s’ennuient le dimanche’ (‘Children get bored on Sundays’).

Unfortunately, the film ‘The Longest Day’ made its own recording of the BBC’s ‘personal messages’, featuring Verlaine instead of Trenet. The film extract is now being shown by the Tourcoing museum, rather than the original BBC recording…

But this museum is not the only one to take liberties with history: others like it refer to ‘blessent mon coeur’ instead of ‘bercent mon coeur’.

A real historian’s work has fortunately been done in an excellent book that explains perfectly why the reference is Trenet’s and not Verlaine’s: by Michael R. D. Foot and Jean-Louis Crémieux-Brilhac, ‘Des Anglais dans la Résistance: Le SOE en France, 1940-1944’. published in 2011 by Tallandier.

![]() Back to D-Day false legends menu

Back to D-Day false legends menu