French resistance in Normandy

Normandy landings – D-Day

Preparation for the organization and actions of the French Resistance in Normandy during World War II, particularly during Operation Overlord in June 1944.

Jedburghs

Materials parachuted to the Norman resistance

Subsidiary operations after D-Day |

Operation Dingson |

It is not easy to define the exact outline of the organization and actions of the networks of the French resistance, their principle of organization based on secrecy and the absence of archives. It is certain, however, that the Resistance played a vital role during Operation Overlord, which began on 6 June 1944 with the assault on « Fortress Europe ».

According to General William Donovan, head of the Office of Strategic Services (US intelligence agency), 80% of useful information during the Normandy landings was provided by the French resistance. Their role, often overlooked, deserves more attention.

- The origins of the French resistance in Normandy

The German occupation of Normandy began in June 1940, four years exactly before the « D-Day ». The first actions of French resistance begin immediately, like the destruction on June 22 of the telephone cable connecting the aerodrome of Boos and the German headquarters of Rouen by Etienne Achavanne: the resistant of 48 years is finally arrested and shot on July 4, 1940. In the months that follow, the first networks come into being and adapt to the occupier. They decided to organize to evacuate the Allied airmen who had fallen in Normandy or to strike the lines of communication such as the railway lines. This is how the « Morpain group », initiated by Gérard Morpain near Le Havre, or the Norman component of the « Alliance » network are born.

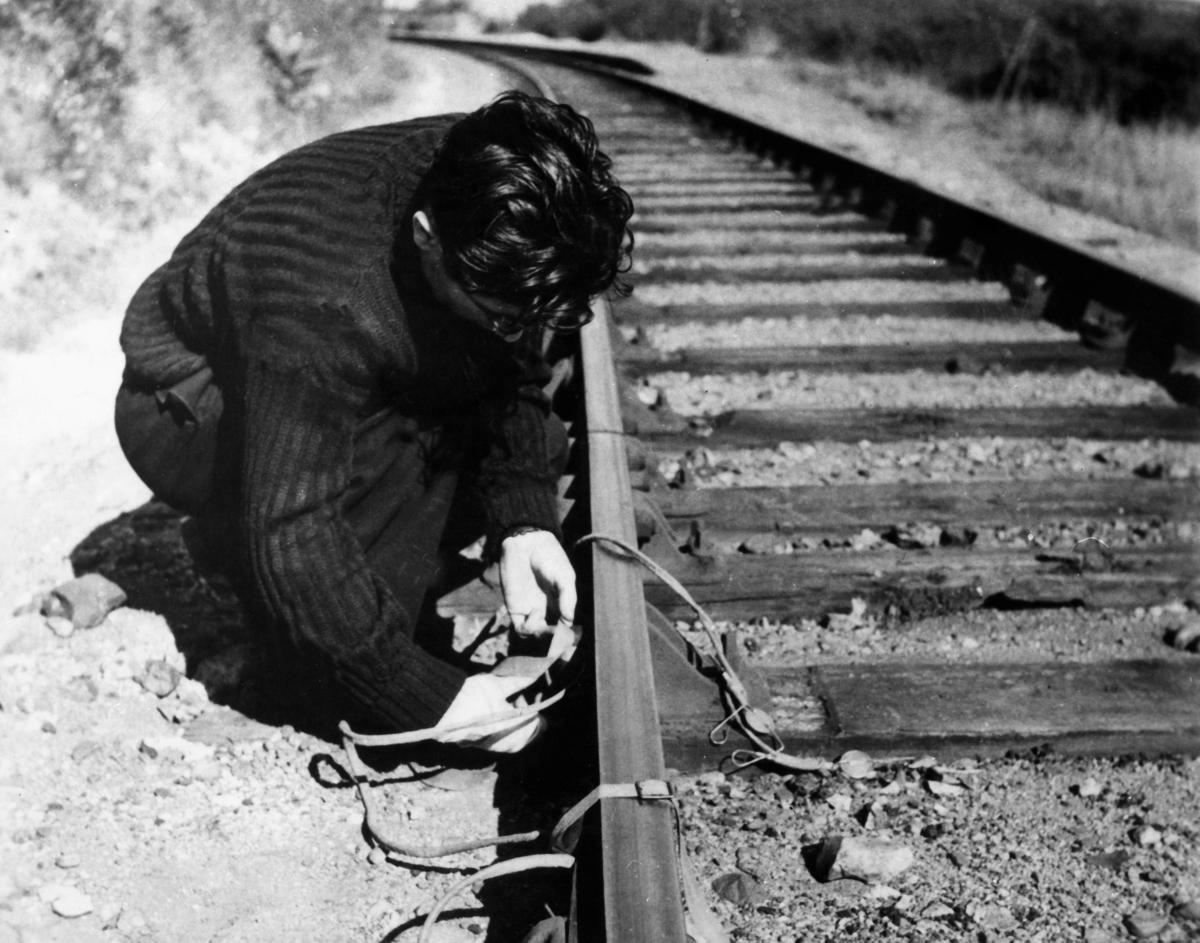

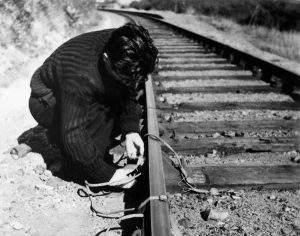

Photo of the derailment of the Maastricht-Cherbourg train on 16 April 1942 in Airan, Normandy, following the dismantling of the rails for several meters by the resistance. 28 dead and 19 wounded are registered by the German soldiers of the Kriegsmarine, returning from permission.

Photo: DR

Normandy, however, is not ideal for the development of refuges (« maquis ») because of its geography and its lack of difficult access plateaus as in the Alps or in the Pyrenees. But some secret sites still see the light, relying on the great forests of the region, such as the maquis of Champ-du-Boult (Commander Berjon) and « Surcouf » (Commander Leblanc).

On February 16, 1943, the Vichy government introduced the S.T.O., the Compulsory Labor Service, which forced thousands of French workers to work for Nazi Germany. This law pushes many volunteers into the ranks of the resistance, which reach the strength of about ten thousand men and women (including two thousand combatants) in Normandy. Faced with this sudden rise in power, the Germans react via its secret police, the Gestapo, which organizes several arrests attacking the main networks at the end of 1943, like the « Alliance » and « Zero-France » networks.

The French resistance also suffers from a multitude of organizations and committees, the number of which partly dilutes the opposition effort against the occupier. The clear and unified lack of command does not allow the resistance to act with all their potential: regional and national political opposition, especially between communists and Gaullists, but also between local groups and those supported by the British, undermine the relations of the combatants.

Nevertheless, on February 1, 1944, the various networks and movements managed to merge to give birth to the French forces of the interior (F.F.I.).

- The relations between the Norman resistance and the Allies

When the Allies prepared their « invasion » of occupied France, at the Tehran conference on November 28, 1943, the French resistance rightly appears to them as still particularly nebulous. As a result, the Allies decide from the outset to prepare military operations without taking into account the military potential of existing networks. While they readily agree to analyze the information provided, there is no question of assigning them any responsibility for the conduct of essential tactical actions, strictly reserved for Allied conventional military forces. The representative of Free France, General de Gaulle, is not even kept informed of the precise preparations for Operation Overlord.

The Allied intelligence services, however, imagine a series of clandestine actions carried out by the resistance to facilitate the conduct of military operations from « D-Day ». These sabotage plans (like the Turtle, Blue, Violet, Red or Green plans) are coordinated in France by the Central Bureau of Intelligence and Action (BCRA), the intelligence and clandestine operations service of the Free France .

Communication, a key point for resistance, is the subject of particular attention with many schemes, both between the Resistance and with the Allies. Messages to London are sent via carrier pigeons and radio transmitters, while Allies broadcast a lot of information to the networks through « personal messages » thanks to the British radio show « London » Broadcasting Corporation (BBC).

Franck Bauer, one of the famous voices of the Radio-London broadcast on the BBC, including the famous « personal messages » of the French who « speak to the French ».

Photo: DR

Because of the secrecy of their organization, the resistance fighters record a cruel lack of anti-tank means and heavy machine guns, which the Allies seek to fill by the parachuting of weapons and equipment. Specialized agents in transmissions, demolition or armaments are also dropped in France, through the S.O.E. (Special Operations Executive). This British special operations command, set up by Winston Churchill, also operates in neutral countries like Spain. Nicknamed « Jedburghs » and organized into a team of three, these agents have the mission to support and advise the Resistance of Europe: they are responsible for information on Allied actions, prepare supplies weapons, ammunition and other materials and install a viable communication system. The Jedburghs are able, if necessary, to take command of the local resistance units.

The Allies do not limit their preparations to Normandy alone: they also plan actions throughout France to slow the progress of German reinforcements. They also want to avoid systematic sabotage in order to preserve certain infrastructures that may be useful to the armies of liberation. For this purpose, precise instructions are transmitted to the resistor.

- The information provided by the French resistance

The main feats of the Norman resistance before the start of Operation Overlord are essentially the acquisition of intelligence. If the Allies do not refrain from making millions of pictures of future landing beaches and landing zones, they receive a lot of information on the terrain, infrastructure, equipment and morale of the occupier.

From the beginning of 1942, the Germans began the construction of the « Atlantic Wall » against the possibility of an allied amphibious assault from England. They set up thousands of defensive positions, relying in particular on the local workforce: in Normandy, resistance fighters engage in various projects to secretly establish plans for these installations; some take the opportunity to slip sugar cubes into concrete mixers to reduce the strength of the concrete bunkers built along the coast. Copies of these plans then arrive in England where they are analyzed and updated by the intelligence services.

The information obtained by the resistance also allows the Allies to refine their degree of knowledge of the German units present in Normandy: the battle orders and the history of the various divisions present are detailed up to the level of the companies, allowing an estimation of their fighting value. Thus, the resisters inform London of the arrival in Calvados of the 352nd German infantry division from March 15, 1944, a unit seasoned by long months of fighting on the Russian front and represents a formidable opponent for the forces Allied.

Captain Kenneth Johnson of the 508th PIR, HQ Co (82nd Airborne Division) interrogates civilians in Ravenoville. His look shows a certain mistrust towards the Normans.

Photo: US National Archives

- Resistance actions on D-Day

In order to increase the chances of success of the Overlord operation, the French networks receive a succession of orders to get into action, essentially through the « personal messages » of the B.B.C. Each coded sentence is sent to a particular network, which knows its meaning and date of execution, in order to begin the sabotage actions and to disrupt the German forces. Thus, from June 1st to 3rd, 1944, the first part of Verlaine’s verse is broadcast on the airwaves: « The sobs long violins of autumn … », along with 160 other « personal messages ». These codes mean that some resistant (here the network « Ventriloquist » installed in Sologne) must be ready to carry out their sabotage actions. On June 5, 1944, at 9:15 pm, the following messages were broadcast: « … wound my heart with a monotonous languor »: the resistors have 48 hours to carry out the destruction. By inference, some networks probably established that Operation Overlord would take place in the next 48 hours.

At dawn on Tuesday, June 6, 1944, after the shock of the bombings and the first fights, members of the networks of resistance spontaneously went to the meeting of the allied forces, sometimes to serve as scouts. Their excellent knowledge of the terrain represented an undeniable added value for dismounted troops and airborne units. However, the Allies were wary of the information they could obtain from the French population and sought first to ensure that their interlocutors were not collaborators who could operate as double agents. Several Normans who approached the liberating soldiers were thus killed by mistake: this is the case of Michel de Vallavieille, 24 years old and future mayor of the village of Sainte-Marie-du-Mont, targeted by soldiers Americans in the Utah Beach area then left for dead. Gustave Joret, a farm worker who gives information to the Allies on June 7 in Surrain, is wounded the same day by an American soldier when he joined a shelter during a bombing. He died of his wounds on June 12, 1944.

In total, nearly 1,000 sabotages were carried out by the resistance from June 5 to 6, 1944. The risks incurred by the resisters during these actions were particularly high: a large number of them had very little military knowledge , and they opposed a trained, seasoned and better equipped army. In the evening of June 6, 1944, the losses of resistance are estimated at 124 killed, wounded, missing or taken prisoner.

However, the sudden and massive nature of these sabotages deeply surprised and helped to disrupt the German forces.

June 7, 1944: A lieutenant belonging to the Civil Affairs of the 5th American Corps talks with Gustave Joret in the area of Surrain, only hours before being seriously wounded by an American soldier. He died as a result of his injury on June 12, 1944.

Photo: US National Archives

- The drama of Caen prison

On D-Day, dozens of French resistance fighters are held by the Germans in Caen prison. While the aerial bombardment adds to the fear of seeing the Allied forces reach the capital of Lower Normandy, the jailers do not want the prisoners to flee to join the attackers. Initially, they plan to transfer them by train to a penitentiary institution in the Paris region. But the railway lines have suffered such degradation that any movement by this means is impossible.

The Germans then receive the order of the Gestapo of Rouen: they must shoot the prisoners. 87 resistant (the youngest being only 18 years old) thus passed by the weapons, in ranks of 6, in the courtyard of the prison. These performances are made in several times, part late morning and then early afternoon.

The bodies are then thrown into a mass grave. While the Anglo-Canadian forces are slow to seize Caen, the resistance is finally exhumed on June 29, 1944 and then moved by truck to a place still unknown to date.

One of the courts of Caen prison where were shot 87 resistant June 6, 1944.

Photo: DR

- The role of the French resistance during the Battle of Normandy

After the landing, the Resistance continued to provide intelligence to the Allies throughout the Battle of Normandy. At the beginning of July 1944, when the front stagnated at the same time as it entered the war of hurdles, the acquisition of information on German positions and devices remained limited; the Allies ask the resistance, via the S.O.E., to obtain a maximum of information. From July 12 to 21, 31 resistance fighters provide information that is immediately exploited by the Americans: bombarding the armored groupings in the south of the Channel, they pierce the front as part of the operation Cobra from July 25.

In order to limit the arrival of future German reinforcements to Normandy after the landing, French commandos were parachuted above Brittany. These side operations took place in June (named Cooney Parties, Lost and Grock) and in August 1944 (Derry), with the participation of 538 paratroopers of the Special Air Service (S.A.S.). They coordinated the various resistance networks to fight effectively against the occupier.

The French resistance fighters of the company Morin at the Saint-Marcel maquis in Brittany.

Photo: DR

Its structural weakness and lack of resources paradoxically made the strength of the French resistance, because the Germans spent a grueling energy to understand its organization and the exact outline of its many devices, without ever managing to put an end to their activities.

General Eisenhower, commander-in-chief of Allied armies in Europe and thirty-fourth president of the United States, had to make the choice between coordinating the actions of the French resistance or favoring excessive actions during the outbreak of Operation Overlord. Because he was struggling to hide his concerns about the success of this daring assault, he finally made the choice of mass sabotage, at the risk of damaging potentially useful infrastructure as a result of the war.

The precise impact of the resistance in the conduct of the Normandy landings is not quantifiable, but there is no doubt that it played a leading role in the success of the Allied armies. According to Eisenhower, French resistance was invaluable during the liberation of Europe in 1944: without its major help, the fighting in France would have lasted much longer and would have caused more casualties in the ranks of the combatants.