Operation PLUTO

Battle of Normandy

- The origins of PLUTO

The P.L.U.T.O. (Pipe-Lines Under The Ocean) program was devised in 1942 by British engineers, in conjunction with allied military personnel, to meet the fuel needs of the armed forces in an amphibious operation. The objective is to set up an underwater pipeline across the English Channel between Great Britain and Normandy after the Normandy landings. The refueling operations carried out by oil tankers are affected by the evolution of meteorology and the possible attacks of German submarines.

|

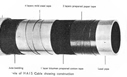

Composition of the HAIS cable equipping some of the PLUTO pipelines. |

Arthur Hartley, chief engineer of Iranian Oil, is the project manager under the control of the Petroleum Wellfare Department. In the long run and depending on the results obtained, this pipeline must also be used in the Pacific. He imagines transforming an existing submarine telephone cable into a pipeline. At the beginning of 1942, two types of pipes were developed: the HAIS model (word obtained from the initials of its inventor) and then the HAMEL model (word composed by the first syllable of the names of the inventors), 75 millimeters in diameter each. These cables are tested in May in the Medway River in Britain and then in June in the Atlantic Ocean off Scotland in the Firth of Clyde. The production of the pipe is carried out in the wake of testing by Siemens Brothers, both in Great Britain and the United States.

|

The “conundrum” around which the pipeline is wound. Photo: IWM |

The pipeline is set up by boat: after being wrapped around a huge metallic drum, called “conundrum” and abbreviated “conus”. The pipe is then unrolled at the surface and lands at the bottom of the sea as the ship progresses. Commercial ships are requisitioned to be processed to receive the kilometers of pipeline to be deployed and a first attempt at sea is made by HMS Holdfast (specially modified for the occasion) from December 26 to 30, 1942, to Linking Swansea to Ilfracombe over a distance of fifty kilometers: it is a total success.

However, the engineers decided to increase the size of the pipe to 76 mm. Plants were requisitioned to produce these pipelines at full throttle: 16 kilometers of pipes were made daily and the British had 550 kilometers of stock.

|

Pipeline winding around the “conundrum”. Photo : IWM |

Other ships are then modified to be equipped with the pipeline. This is the case of HMS Sancroft and HMS Latimer, capable of transporting 160 km of pipe. A flotilla is specially dedicated to the establishment of PLUTO, with a hundred officers and about a thousand sailors, technicians and workers. These men, based mainly in Southampton, are commanded by Captain J. F. Hutchings.

|

Diagram of conditioning of the pipeline around the “conundrum”. |

- Operation Bambi

In 1943, operation Bambi was launched: the Allies wanted to equip themselves with all the necessary equipment to connect the Isle of Wight and the port of Cherbourg after landing in Normandy. Pipelines and pumps to propel the fuel through the pipelines are then installed in the ruins of the Royal Hotel in Shanklin as well as in civilian seaside buildings, deliberately neutral and made up in shops to avoid attracting attention.

|

Flow of the pipeline at sea. Photo: IWM

|

A general rehearsal of the installation of the PLUTO towards Normandy is realized in order to connect the localities of Swansea and Watermouth, distant of 83 km.

|

Flow of the pipeline at sea. Photo: IWM

|

- The installation of PLUTO to Normandy

Operation PLUTO in Normandy is divided into three phases: first, oil tankers make the return journey between Great-Britain and the Normandy coasts, supplying the Allied forces thanks to pipelines disposed between the coast and the sea. Subsequently, submarine pipelines are installed at the bottom of the English Channel and directly connect Britain and Normandy. Finally, in a third phase, a new pipeline network (Operation Bambi) is set up between the Isle of Wight and Querqueville, west of Cherbourg, thus avoiding the tankers multiplying the crossings. The Cherbourg device is also known as the “Major System”.

|

HMS Latimer hose flow. Photo: IWM

|

Towns designated to receive fuel depots for the second phase of operation PLUTO are Port-en-Bessin and Saint-Honorine-des-Pertes, located at the geographical center of the Normandy landing beaches. The installation of the Minor system began on 9 June 1944 and after several weeks of work, pipeline refueling could be carried out.

From 12 to 21 August 1944, more than two months after D-Day, the pipeline between Shanklin China (on the Isle of Wight) and Querqueville is installed, connecting Britain to Normandy for a distance of 130 km. The pipeline network then developed on land, following the evolution of the front line and supplying fuel depots such as La-Haye-du-Puits, Lessay, Saint-Lô and Vire.

|

Supply of pipelines in England, protected from air sight and attacks. Photo: IWM

|

In Normandy, the Allied Gasoline Service can be used directly at the pump and thousands of jerrycans are aligned to receive the precious fuel. Once loaded on trucks, jerrycans are distributed to the operational units and the refueling circuit continues.

Thereafter, no fewer than 17 pipelines were set up (11 HAIS models and six HAMEL models) between Great Britain and the Pas-de-Calais (from Dungeness to Ambleteuse).

|

HAMEL pipelines installed in France. Photo: US National Archives

|

In January 1945, 305 tons of fuel crossed the English Channel daily, followed by 3,048 tons in March and 4,000 tons in May. In total, between August 1944 and May 1945, 781,000 cubic meters of fuel made the Great Britain-France submarine route.

In September 1946, HMS Latimer (renamed Empire Ridley after the end of the Second World War), HMS Holdfast (renamed Empire Taw), Empire Tigness and Redeemer, began operations to disengage pipelines. The sale of the recovered cables has made more profits than expected and has largely covered the disengagement costs.

|

A “conus” abandoned on a beach in Britain after the war. Photo: IWM

|

Today, remains of the PLUTO pipeline still exist, including dozens of meters of elements of operation Bambi at the bottom of the Channel, as well as on the Isle of Wight. Indeed, 10% of all oil pipelines have not been recovered.