Was Gondrée House really the first house to be liberated on D-Day?

The false legends of D-Day

In the background behind the Bénouville bridge, the Gondrée house (white shutters closed) represents one of the most widespread false legends of D-Day.

Photo: IWM.

False D-Day legend: ‘Gondrée House was the first house liberated on D-Day’.

Rarely has a legend been so tenacious. Throughout the year, visitors flock to discover the self-proclaimed ‘first house liberated on D-Day’ in Bénouville, located in the immediate vicinity of the famous Pegasus Bridge, a bascule bridge captured by the airborne soldiers of the 6th Airborne Division in the early hours of 6 June 1944.

However, no historian specialising in the Battle of Normandy is in a position to confirm this. On the contrary: factually, everything points to the fact that this house remained inaccessible to the Allied fighters for several hours after the assault began.

The notion of ‘first house liberated’ or ‘first commune liberated’ is not of great historical interest. This claim was not made by the Allies in any way, but exclusively by the French, proclaimed a few hours, days or sometimes months after the event.

So what happened on 6 June 1944 in Bénouville? The ‘Pegasus’ bridge over the Caen canal was the objective, in the very first minutes of D-Day, of 90 fighters airlifted by gliders and belonging to the 2nd Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry, the 249th Field Company Royal Engineers (Airborne) and the 7th Parachute Battalion (5th Parachute Brigade). The aim of this night action (under the command of Major John Howard) was to protect the eastern flank of the future Allied bridgehead in Normandy by controlling this key crossing point in order to prevent any enemy counter-attack from this sector. The 90 men were divided into three sections aboard Horsa gliders, which were to land in the immediate vicinity of the bridgehead. At the same time, three other gliders were to be deployed to seize another bridge over the River Orne.

According to Major Howard’s assault plan, Lieutenant Herbert Denham Brotheridge’s No. 25 Platoon was to land first to clear the shelters on both banks of the canal while taking the furthest positions on the west bank of the Caen Canal. Lieutenant David Wood’s No. 24 Platoon was tasked with clearing the trenches of Wn 13 along both banks of the canal before linking up with the other British troops engaged in seizing the bridge over the River Orne. The No. 14 Platoon under Lieutenant Richard Smith was to reinforce the No. 25 Platoon to the west of the bridgehead and hold out against possible enemy counter-attacks. So, in theory, it was the No. 25 Platoon that was likely to reach the first French dwellings in the sector, all those to the east of the bridge having been razed to the ground by the occupying forces before D-Day.

Horsa glider number 91, piloted by Staff Sergeant James Wallwork and Staff Sergeant John Ainsworth, was the first to land: it was 0.16 am. On board were Major Howard and his radio officer, Corporal Edward Tappenden, as well as 21 soldiers from No. 25 Platoon and five sappers. After a brief period of reorganisation, Lieutenant Brotheridge launched his assault, shouting ‘forward 25th’: it was 0.18 am. The first shots were fired.

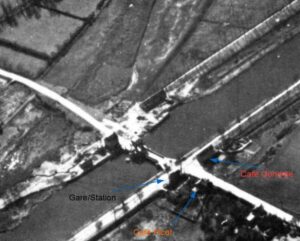

Aerial photo showing the Pegasus Bridge, the tram station, Maison Gondrée and Café Picot.

Photo: DR

Within seconds, Private William Gray had crossed the bridge and approached his objective: the small building of the Bénouville tram station on the canal bank at the northern corner of the crossroads. He threw a grenade inside, waited for it to explode and then fired a burst from his machine gun. The station, which could be the first building in mainland France to be liberated by the Allies, was empty. Gray left the scene and then moved on to the site of an anti-aircraft gun to the west of the bridge.

The shutters and front door of the Gondrée house remained closed and the occupants rushed to the cellar to take cover.

However, at the same time, other residents of Bénouville ventured outside their house, imagining that the military manoeuvres they had been informed about a few days earlier were taking place in front of their house. In fact, training had been planned by a regiment of the 21. Panzerdivision on the night of 5 to 6 June. While most of the residents thought they heard the sound of training ammunition, this was not the case for Louis Picot, the owner of a café, who immediately understood the importance of the events in progress. Still in his dressing gown, he came out of his house to watch the fighting, waving to Lieutenant Brotheridge’s men and shouting ‘Long live the English! The airborne soldiers then rushed to search the houses they could get into: first they inspected the Picot family’s house before entering ‘La Chaumière’. Inside was the Niepceron family, whose father was the bridge operator on the bascule structure.

At 0.26 am, just ten minutes after the first glider had landed and eight minutes after the start of the assault by No. 25 Platoon, calm had returned, leaving only the occasional gunshot. The Gondrée family was still holed up in the cellar, with all openings closed.

At 0.52 am, Brigadier Nigel Poett, commanding the 5th Parachute Brigade, reached the Ranville bridge after parachuting north of the village of Ranville and then headed for the Bénouville bridge, beginning the relief of Major Howard’s men.

At first light (between 5 and 6 a.m.), the British went door-to-door to inspect the buildings at Bénouville and make sure there were no enemies at the heart of their position. They knocked on the door of the house next to the canal: Georges Gondrée, the owner of the premises, which had remained closed until then, opened the door with some trepidation to the two soldiers. They quickly inspected the house and discovered the family had been hiding in the cellar since the fighting began.

The building was transformed into a medical unit a few hours later, under the orders of Captain Urquhart, and received many seriously wounded.

Results of the fighting at Bénouville on 6 June 1944.

At the end of my research, based on military reports supplemented by eyewitness accounts from those directly involved in the events, there is no evidence to suggest that Gondrée House was the first house to be liberated in the fighting at Bénouville on 6 June 1944.

On the contrary, several other buildings in Bénouville were obviously ‘visited’ by British soldiers (starting with the tramway station, which has now disappeared) before the door of the Gondrée family was opened at dawn on D-Day. And if we take into account all the fighting in Normandy by American and British paratroopers between 1am and 5am, the likelihood that the Gondrée house was actually the first home liberated in France (on the mainland, it should be noted, as Corsica had already been liberated) is even smaller.

And yet, despite all this evidence, the legend of the self-proclaimed Maison Gondrée continues to exist.

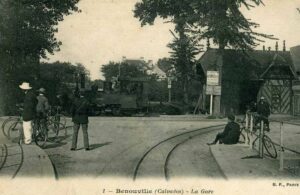

Postcard illustrating the Bénouville tramway station (no longer in existence), probably one of the first houses liberated in mainland France on 6 June 1944.

Photo: DR

Marc Laurenceau

Sources and bibliography:

2nd Battalion Oxford and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry War Diary, 1944.

HUGEDE Norbert, Le commando du pont Pégase, éditions France-Empire, 1985.

BARBER Neil, The Pegasus and Orne Bridges, Pen & Sword Military, 2009.

LAURENCEAU Marc, Historial du Jour J et de la bataille de Normandie, 6 juin – 25 août, OREP, 2024.