Speech by Nicolas Sarkozy

65th anniversary of the Normandy landings

Colleville-sur-Mer American Military Cemetery – 6 June 2009

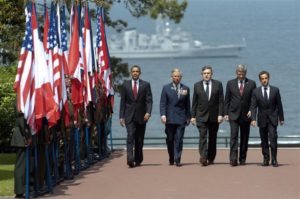

Barack Obama, Prince Charles, Gordon Brown, Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper and Nicolas Sarkozy at the cemetery in Colleville-sur-Mer.

Photo: Official White House.

“Mr President of the United States of America,

Your Royal Highness,

Prime Minister of Canada,

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland,

Prime Minister,

Presidents of the Senate and the National Assembly, Ministers,

Members of Parliament,

Madam and Sirs Ambassadors,

Mr President of the Regional Council,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

There were 135,000 of them on thousands of boats.

They formed two armies: one American, the other British and Canadian.

A few hours earlier, Eisenhower had wished them ‘Good luck!’.

Everyone was silent.

What were these young soldiers thinking as they stared at the thin black strip of coastline gradually emerging from the mist?

Their short lives? The kisses their mothers tenderly placed on their foreheads when they were children? Their fathers’ tears when they left? Those waiting for them on the other side of the sea?

What were these young soldiers thinking, whose destiny had placed the fate of so many peoples in their hands, if not that 20 was too young to die?

Their silence was like a prayer.

On the beaches, 50,000 Germans were waiting for them, also in silence.

It was a fateful moment.

The day before, the Resistance had blown up 500 bridges. Between midnight and 2:30 a.m., paratroopers from the 82nd and 101st American Airborne Divisions and the 6th British Airborne Division had been dropped behind the front lines.

Between 3:15 and 5 a.m., 5,000 bombers pounded the entire coast.

At 4:15 a.m., troops began to be transferred to the landing craft.

At 5:45 a.m., the guns of 1,200 warships opened fire.

At 6:30 a.m., the landing began.

The wind was blowing hard. The barges were tossed about by waves several metres high. The soldiers were soaked, shivering with cold, sick, bailing water with their helmets. Those who disembarked too early drowned. Boats sank before reaching their destination. Of a total of 19 tanks, a Canadian armoured unit lost fifteen before reaching the beach.

Those who made it to the beach landed among the dead and wounded floating in the water, carried by the tide. Then they had to step over the dead lying on the sand. One of the first American soldiers to land at Omaha Beach wrote: “It all seemed unreal, like a waking nightmare […]. You could almost walk the entire length of the beach without touching the ground littered with bodies.”

Opposite him, the German soldier firing at him with a machine gun experienced the same feeling of horror as he looked ahead at ‘the bloody muddy expanse where hundreds and hundreds of lifeless bodies lay.’

By the evening of 6 June, more than 120,000 Allied soldiers had been landed, in addition to 32,000 men from the airborne divisions. Among their ranks were more than 10,000 dead, wounded or missing. The General Staff had anticipated 25,000…

By the evening of 12 June, after six days of relentless fighting, the Allies had managed to establish a continuous front line 80 km long and 10 to 30 km deep.

But the Battle of Normandy would last until 29 August.

By that date, two million Allied soldiers had landed, 38,500 had been killed, 158,000 wounded and 19,000 reported missing. The Germans had lost 60,000 men killed, 140,000 wounded and 210,000 taken prisoner. Nearly 20,000 civilians will have lost their lives.

The Battle of Normandy decided the fate of the war. It was won on the beaches and in the sunken lanes of the bocage by the sons of American farmers and labourers whose fathers had fought in the Meuse and Argonne in 1918, by British soldiers who embodied the heroic virtues of a great people who had not given in during the most terrible ordeal in their history, and by Canadian soldiers who had volunteered from the very first days of the war, not because their country was threatened, but because they were convinced that it was a matter of honour.

The Battle of Normandy was won by the soldiers of the 1st Polish Armoured Division engaged in the fighting in the Falaise pocket, who covered themselves in glory by repelling the German counter-attack on 19, 20 and 21 August 1944, in which 2,300 of them were killed or wounded.

The Battle of Normandy was won by Czech, Danish and Norwegian airmen, Belgian and Dutch paratroopers, Leclerc’s soldiers, Kieffer’s commandos and the SAS fighting in British uniform.

The Battle of Normandy was won by 20-year-old soldiers who killed so as not to be killed, who were afraid of dying, but who fought far from home with admirable courage against a ruthless enemy as if the fate of their own homeland were at stake.

The Battle of Normandy was revenge for Czechoslovakia and Poland, which had been carved up, for Belgium and the Netherlands, which had been subjugated, and for France, which had been defeated in five weeks. It was revenge for Sedan, Dunkirk and Dieppe.

Before the nine thousand American graves in this cemetery where we are gathered today, Mr President of the United States, I would like to pay tribute, on behalf of France, to those who shed their blood on Norman soil and who lie here for eternity.

I would like to thank the last survivors of this tragedy who are here today and, through them, all those whose courage made it possible to defeat one of the worst barbarities of all time. They fought for a cause that they knew in their hearts was greater than their own lives. Not one of them backed down.

We cannot name them all, these heroes to whom we owe so much.

There were so many of them.

But we will never forget them.

Among them, Mr President, were your grandfather, a sergeant in the US Army, and his two brothers.

For all French people, therefore, you are twice the symbol of the America we love, Mr President: through your office and through the blood that runs in your veins.

The America that defends the highest spiritual and moral values.

The America that fights for freedom, democracy and human rights.

The America that is open, tolerant and generous.

Mr President of the United States, Mr Prime Minister of Canada, American and Canadian soldiers came to fight alongside the British and French twice. What would have happened if they had not come? From this question, whose answer was so obvious and so tragic, Europe was born.

Faced with so much destruction and so many coffins, everyone understood that the vicious cycle of revenge, which in every war sowed the seeds of the next and had brought the peoples of Europe to the brink of annihilation, had to be stopped.

So we made peace and we built Europe to last forever. We owed it to all the innocent victims. We owed it to all those young soldiers who had sacrificed themselves for us. We owed it to our children to spare them the same suffering. We owed it to all the people whom Europe had dragged into its misfortunes.

All those who had fought against Nazism and fascism had done so with the dream of building a better world where law would replace force.

We know how far we still have to go.

We know that the road ahead is long and difficult.

But we also know what a united Europe and an America faithful to its values can achieve together. The great totalitarian regimes of the 20th century have been defeated.

The threats facing humanity today are of a different nature. They are no less serious.

What will become of the world if global warming deprives hundreds of millions of men, women and children of water and food? If speculative capitalism destroys the jobs of millions of people? What if extreme poverty drives part of humanity to despair?

What would become of the world if, through cowardly abandonment, democracies were to leave the field open to terrorism and fanaticism? What if they gave up defending human rights and the rights of peoples?

The ideal of the United Nations was born out of the struggle of free peoples against Nazism. Our duty, Mr President, is to bring this ideal to life. Otherwise, what will have been the point of so much bloodshed, sacrifice and suffering?

The heroic dead who lie here must not belong only to history. The finest tribute we can pay them, perhaps the only one that really matters, is to strive to be worthy of what they accomplished for us.

When Sergeant Bob Slaughter found himself on Omaha Beach on 7 June 1944, where he had landed the day before, he was all the more shocked by the sight of all those men being swept away by the waves because he had known them since childhood and had grown up with them. A thought then crossed his mind: ‘We were brothers, and we always will be. They died so that we could live. I thank them for what they gave us.’

Throughout his life, he remained haunted by ‘those stern faces, eyes and mouths wide open, fixed in the coldness of death.’

Like the German sergeant, Hein Severloh, who “since that time, always and without ceasing, saw a lone GI emerging from the grey waves of his dreams and landing there on the beach. He shoulders his rifle, aims and fires. His helmet rolls as if in slow motion, spinning over the sand, bathed in the waves that come to die at the edge, then slowly the soldier collapses and falls face down…”.

Just as the American soldier who, in Dachau or Buchenwald, first met the haunted gaze of a deportee stunned to have survived hell never forgot it.

He had just understood why he had fought…

From all the suffering they carried within them and could not shake off, the combatants in this atrocious war drew a great dream of justice and peace.

May we, Mr President, never forget what that suffering was like, nor give up on that dream.

May we share that dream with our children. That great dream of Justice and Peace.”

![]() Back to D-Day 65th anniversary Speeches menu

Back to D-Day 65th anniversary Speeches menu